Steve Switaj

Basic Member-

Posts

81 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Everything posted by Steve Switaj

-

Does anybody know where Red used to get their lenses? The large stop motion company that I work for is circling around the idea of upgrading our lens fleet for upcoming projects. Our needs are not really that weird, but still specific enough that we end up remounting or even rehousing much of our glass, and, it's a pain. The number of lenses we're thinking of buying is large enough that we may be justified at looking at some semi-custom options, so I'm gathering names of vendors to talk to. Anybody have any leads?

-

Stephen, I think we need some more information here to figure out what you're after. There are (basically) three kinds of lens adapters. The first one is purely mechanical, a short tube with a flange on either end, meant to mount a lens with a deep flange (backfocus) depth to a camera with a shallow flange depth. It simply holds the lens in place at the correct distance from the film plane and fills up the space in between. These adapters do not have any optics in them, and, if made accurately, allow the lens to focus to infinity. They are commonly found adapting a still lens to a small-format cine camera. They don't affect the size of the image at the focal plane or the image brightness, though you may see a "crop factor" because you're on a smaller sensor, and what was once a normal lens on your 35mm still camera now crops down to a mid-telephoto in super 16. The second type is mechanically like the first, but with active optics in the tube. This type can shift the focal plane around or shrink/grow the image. For example, I have a PL-to-EF adapter that goes on a cine zoom and expands the academy-sized image to cover a full-frame sensor, at the expense of creating an image one stop dimmer (because it's spreading the same light over a larger area). There are "speed increasers" that go the other way, shrinking a full-frame image down to an APS-C or 4/3 frame size. Since they take the image and concentrate the same light over a smaller area, the image gets brighter, but there is no crop factor (because the image is smaller). The third type is exclusively a play for macro focus. These are usually purely mechanical, like type 1, but they purposely have way more than the "correct" amount of back-focus, usually by 10-50mm or so. By spacing the lens out farther than normal they basically extend the focusing threads allow additional close focus, but at the expense of no longer being able to reach infinity (because the lens can't get back far enough any more). Think of them like old-school extension tubes on a still camera. Sometimes these macro tubes can employ a second helicoid to make them adjustable and thus more versatile. This type of tube definitely will affect your image brightness. Effectively, you're moving the focal plane farther from the lens, and the inverse-square law will start to come into play. The effective focal length will also seem to grow as you focus closer. These are both results of the basic laws of optics, but since they are exponential you usually only notice them in macro work (many true macro lenses have barrel markings to indicate this shift, btw). Look up "bellows factor" from still photography for a better explanation. In your case you probably have two normal "type 1" adapters. The first goes from the 66mm backfocus of a Hasselblad lens down to the 46mm backfocus of an M42 camera body, and the second goes from the 46mm backfocus of an M42 standard lens down to the 40mm backfocus of the Aaton mount. Assuming there's no glass in there, and you can focus to infinity, your exposures should not shift (though your Hassleblad still lens will be marked in F-stops instead of T-stops, so you might want to dial in an extra half stop or so)

-

Well, don't forget that anamorphic lenses actually have two focal lengths, one in the horizontal axis and one in the vertical axis. The mumps effect and bokeh smearing and general weirdness that you sometimes see when there's a strong focus pull is largely the result of one lens trying to be a 35 in the horizontal plane and a 70 in the vertical plane.

-

Nikon to Acquire US Cinema Camera Manufacturer RED

Steve Switaj replied to Jeremy Saltry's topic in Cinematography News

This is interesting. If you've been to NAB in the last decade it's been clear that Nikon has been trying to get themselves a little of the video-side action like Canon. About 5 years ago they bought the VFX motion control company Mark Roberts. They didn't really explain why, and it seemed an odd fit. But then I saw the two companies had a combined NAB booth that showcased their joint foray into remote-operated camera heads for high-end sports and automated camera pedestals for smaller news broadcasts, all featuring tight integration with Nikon DSLR's instead of the more typical video cameras you might expect. It made sense, Mark Roberts needed funding to explore markets other than the slowly evaporating film VFX world and Nikon really had to find a way to grow their photo division out of their limited (mostly) still camera market. Canon always had first mover advantage since they already had a toehold in broadcast and film with their lenses, and their consumer and prosumer video products going back to the 80's gave them a product line to build on. But Nikon has never really had that. Yeah, they build microscopes and sport optics, but on the photographic side... they're mostly a still camera company. Now that everybody with a phone - which is to say pretty much everybody - already carries a pretty good camera in their pocket all day long, I've got to believe that the niche for dedicated still cameras is getting pretty dang tight, at least by historical standards. Nikon kind of has to do something, it can't let Canon keep gobbling up market sectors. -

Abrupt change in camera exposure

Steve Switaj replied to Stewart McLain's topic in General Discussion

Well, you mentioned 'alleyway' and 'extant lighting' Maybe the lighting was some type of discharge lighting or LED's and was strobing at the power supply frequency. That's not uncommon in the lamps used in 'high efficiency' area-type security lighting. If you were in a place with a 60Hz supply, that would mean that you had a 60 or, more likely, a 120Hz strobe, which is a nice multiple of a 24, 30 or 60 FPS frame rate. A 60 Hz strobe should be noticable, but a 120Hz strobe might not be visible to the human eye. But to a camera that exposes each frame for a few millliseconds, it would make a difference. If you were shooting with a narrow enough shutter angle (like you went up to 1600 ASA, and the camera compensated exposure by reducing the exposure time) you could find your exposure time getting smaller than one light cycle time and your image sampling falling in and out of phase with the lighting. Sometimes you might start recording and find yourself exposing in phase with the lights while they were on, sometimes you would start recording and this time you were out of phase and exposing when the lights were off. -

How about Ken Stone up in Fraiser Park? http://stonecinema.com/

-

How about this series of JIS screws at McMaster-Carr https://www.mcmaster.com/catalog/129/3396/94387A514 They're JIS standard, which means the heads are a bit thinner and less wide than the typical metric series (1.3 x 3.5mm versus 1.7 x 4.0mm) I use them for installing Nikon and Canon lens mounts on the specialty optics we build at work. In 2x6mm they're about $4.71/50

-

What he said, the fotodiox part. Really, a damn good adapter for $43. https://fotodioxpro.com/products/ab-c-p?_pos=4&_fid=c1012711a&_ss=c

-

movies that talk about film making

Steve Switaj replied to Abdul Rahman Jamous's topic in On Screen / Reviews & Observations

I remember "And God Spoke" from 1993 In theory a comic mocumentary about the making a big Biblical epic, but in practice actually a documentary of every real film I've ever worked on. -

The best option is probably an unconverted Mitchell GC or standard. They're not even a little bit sexy, but they're inexpensive, readily available, and have rock-solid registration if they've been even minimally maintained. Their focal-plane shutters offer really good light sealing, so they are useful for time-lapse or animation, and they won't become a leaky mess when you stop them and they have to sit for a moment while you calculate out how far you want to backwind. They are almost purely mechanical, but there have been a variety of motors produced by 3rd party companies for everything from stop-motion to high speed. Most of these cameras use an external spring-belt for mag drive. This can be switched from the takeup side to the supply side to run backward. the Standard model (with phenolic gears) is good to at least 36fps, while a GC (with metal gears) will run all day at 120fps if you keep the movement oiled. Both cameras will happily run in reverse at 24 fps. We used to use these cameras all the time for motion control work, an often ran the film back and forth several times to build up exposure layers, like, on a spaceship where you might have one hero "sunlit" exposure, then turn the key lights off, backwind the film, and re-expose a long exposure to burn in the portholes.

-

Supposedly, every Mitchell 35 ever made had an 8:1 shaft with an accessible D-spline that could be hand cranked. I know for a fact that this is the case with the Fries Standard conversion sitting on sticks in the corner of my living room, and that was one of the last Mitchells off the line, built in 1974. Don't know about their 65-5perf line, but from what I can recall those were mostly just upscaled NC's. I have personally never hand-cranked a camera, but was once told by an olde-timer that you should mentally hum the "Addams Family" tune to keep time.

-

You shouldn't have to compensate anything. The maker made it so that the shutter is open for .75 seconds. The prism will take 1/3rd of the light, leaving 2/3rds of the light through to the film, so your effective exposure time as seen by the film is 0.75sec * 2/3 = 0.5 seconds. 1/2 second, conveniently, is an easy number to work with photographically, and probably why the builder chose that weird .75 sec mechanical shutter time in the first place. So treat your Bolex as if it is a still camera with a fixed 1/2 second exposure time. Set you meter to sill mode, dial in 1/2 second exposure, and adjust your aperture and ND accordingly. All this assumes that your lenses so not have iris rings marked to pre-compensate for the prism loss (Bolexes are not my specialty, so maybe someone can chime in) if the lenses are marked to take the prism into account, then set your meter to the speed between 1/2 sec and 1 sec, which is technically .707s but may be listed as .7 or 3/4, either way it's close enough to make no difference. they key thing is that your movie camera is now a still camera with a fixed exposure time, and you have to calculate aperture and ND as if you're taking stills

-

Also, I would note that sometimes there are auxiliary cameras attached to the main camera. I used to do a lot of VFX and it was common for a movie with extensive facial replacement to rig two small witness cameras out a few feet on either side of the film camera, converged a couple of yards in front of the lens. These would be recorded and provided to the VFX people to help them understand what the actor was doing in the Z axis.

-

It's not attached to the main camera, it's in the hands of a set photographer, crouched in the lower center of the frame. You can see her(?) right hand supporting it. Feature films often employ a separate still photographer to generate all the publicity materials, and sometimes they photograph right along side the regular film crew. Though it's not as much as an issue today, in the days of film you wouldn't want to use a still taken from the motion picture camera - you'd have to cut (or at least dupe) the camera negative, and a 4-perf frame is tiny for a still. This photo is from 2007, so the camera is likely a DSLR, either film or digital, and so it makes noise when it shoots. Hence the photographer has enclosed it in a blimp, which is why it looks so big an boxy.

-

There was a bit of a scandal in the still photography world back in the 90's about the performance of the medium-format Zeiss lenses. One of the medium-format camera companies (I think Bronica) was looking to sell more of their cameras, and their research showed that the biggest issue stopping advanced amateurs from moving up to medium format was the cost of a set of lenses. At the time, Bronica, like Hasselblad and Rollei, all used the same exact lenses, all made by Zeiss but sold in different mounts by each manufacturer. So Bronica contracted with a Japanese manufacturer (Tokina, I think) to build a line of "budget" lenses. But the thing is that Zeiss had been cruising for years on legacy designs, some of which dated to the 50's. And while I love that beautiful Hassleblad glass, the decades without competition left Zeiss with a design refresh cycle that was... well, let's just call it a less than enthusiastic Tokina, on the other hand, started with a clean sheet of paper and the latest optical technology available in the 90s. Buyers soon noticed that the "budget" lenses were noticeably sharper and contrastier than the (much) more expensive Zeiss-built "professional" lenses.

-

Arri 16SR - External variable speed control

Steve Switaj replied to Bernhard Kipperer's topic in 16mm

8 pin? Dunno about that one, but the Arri 11 pin is here https://flywom.com/support/support_files/Film camera accessory connectors.pdf -

Cinemax Macro C-802 Super-8 - Mercury battery

Steve Switaj replied to Mario Hatzopoulos's topic in General Discussion

Mercury batteries were popular in the 60's and 70's for photographic gear because they had a flat discharge curve and a long shelf life. So, basically, they provided a consistent voltage for a long time in intermittent use, and that's a good match for the demands of photo equipment. Though they were good at their job of being batteries, the downside was that oxides of mercury are very neurotoxic, and dumping all those batteries into landfills was... problematic. So... where do we go now? Well, first, there's no such thing as a 3.9v mercury battery. The basic chemistry of a mercury oxide battery provides a cell at about 1.35v, so as Joerg notes your battery is almost certainly 3 cells stacked in series in a common wrapper. It probably provided about 4.05v when new and unused, and settled in at about 3.9 v under it's rated load (little coin cells tend to have a pretty high internal resistance) Probably the best match for the voltage and discharge curve of mercury today is a zinc-air battery. These are the types of batteries you see sold for hearing aids. They have a little plastic tab on the top that you peel away to allow air into the battery. Oxygen in the air starts reacting with a zinc compound inside the battery and... well... it batts. They have an almost identical voltage, good power density, and a reasonably flat discharge curve, but they don't have anything like the lifespan of mercury. If you can get a good measurement of the battery size, you could probably improvise a holder for three cells. The thickness is the important part, you can always pad the diameter. Look here for common sizes... https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_battery_sizes#Zinc_air_cells_(hearing_aid) Depending on how finicky your meter is, you might also be able to use three silver oxide cells. That would be a lot more convenient because silver oxide cells come in more sizes than zinc-air cells. Basic silver-oxide chemistry is about 1.5 volts/cell, though, so a stack of three is 4.5v. The extra voltage is unlikely to damage your equipment, any good engineer would build in a lot more margin than that, but depending on the circuit it may affect accuracy. Common sizes of silver oxide cells can be found here... https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_battery_sizes#Silver_oxide_and_alkaline_cells -

Dom; What it the big blue camera?

-

-

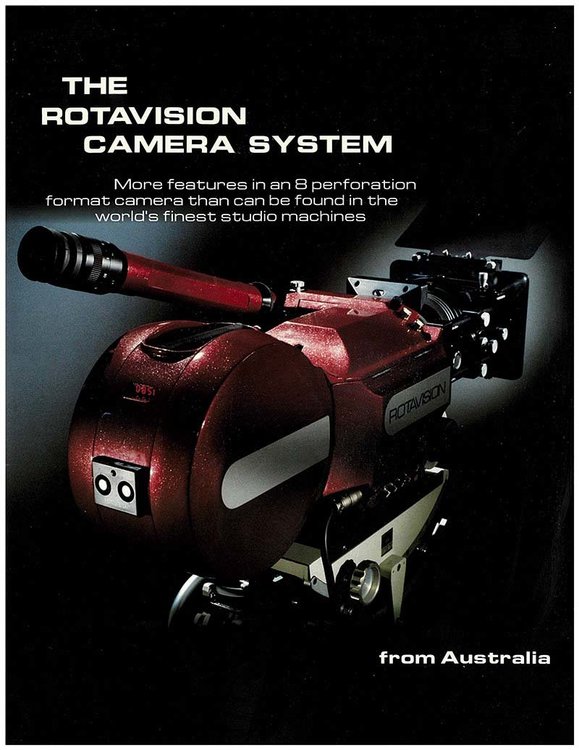

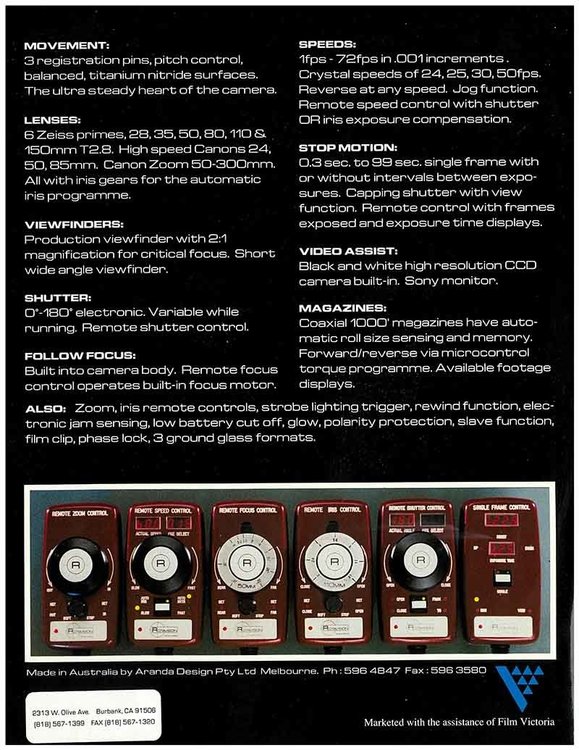

There was one stab at making a modern sync sound VistaVision camera that I know of, built by an Australian company called Rotavison in the 90. It was a true fresh build, from the ground up. I played with one once, It seemed like a really solid system, but I never did see one “in the wild” so I don’t know if they ever sold any. It was really advanced, though, it did 72FPS and came with a selection of accessories that rivaled the contemporary 4-perf models. It used its own proprietary lenses, and included a drive mechanism in the body for remote focus and iris control. Like I said, I never saw one used, but considering the small fortune it must have cost to build up the prototypes with all their accessory systems, I hope they sold some somewhere

-

I spent 20 years shooting motion control and VFX and got very familiar with VistaVision. It was pretty popular from the late 80’s up to the mid 00’s. The same advantages that drove it in the 50’s were very applicable to its use in visual effects . Back in the day Vista had a logistical edge because unlike the 65mm, formats, labs in any big city could develop your dailies, and unlike early anamorphic lenses, the flat Vista lenses produced much more flattering results on actors at moderate and close distances. In the FX world of the 90’s You got a larger negative, but it still used 35mm film, which meant that you could use the same stock and labs as the rest of the units were using. Also the lenses were spherical. If you were working on an anamorphic show, you could have VFX plates with much less distortion. But since only one studio used it, there were very few VistaVision cameras ever produced, probably less than 20. The camera at the top of the page is one of Greg Beaumont’s VistaVision conversions. Greg was the in-house camera engineer up at ILM for many years (I think he’s still an active partner at 32ten). He built a couple of Vista cameras for ILM over the decades, but IIRC he had a side gig and built about a half-dozen of these “BoCams” on his own. They were used extensively in VFX work throughout the 80’a and 90’s Greg rehoused the original 1950's Mitchell movements in a new reflex body. The BoCams used Arri-III mags and were driven from below with what looked like a modified Cinema Electronics Arri-II base. They were good, simple cameras and ran well. If they had one weakness it was that the motor in the base seemed a little short on grunt sometimes, and without big batteries you could get into problems with rapid camera motion causing the film reels to drag inside the 1000’ mags which, in fairness, were probably not designed to run on their sides. Mitchell made a small handful of ‘real’ studio cameras, the “elephant ear” models you see in the old behind-the-scenes still from Hitchcock movies. They also built about 3 lightweight ‘butterfly’ models. Coming in at a svelte 17 lbs these were intended for MOS action shots. Rumor has it they were commissioned for the chariot races in Ben Hur. Additionally, Mitchell converted another handful of the old three-strip Technicolor cameras to shoot Vista, basically removing the complex technicolor movement and replacing it with an 8-perf unit. When I first heard of this it sounded crazy, but with only one strip of film to handle, the original boxes had plenty of space for the 90 degree turn, and all the other film-handling infrastructure was already done. I got to handle one of these Technicolor conversions at Bray studios in Ireland. It was BIG. I think very few of the original cameras survive. On the plus side, most of the small fleet got to shoot again in the 80’s and 90’s, but on the minus side, most of these cameras lost their original form, with the only movements being preserved and rehoused in “modern” bodies. Greg Beaumont did (I think) about 6 BoCams, while Doug Fries did two or three conversions. ( I got to rebuild the electronics on one of the Fries VistaVision cameras last year, I wrote up the story on Hackaday… https://hackaday.io/project/186456-vistavision-camera-electronics-rebuild ) ILM also did 2 or 3 reflex conversions they called VistaCams or something similar. I don’t know how efficient they were (they were some of the earliest conversions) but they were really cool since they had a neat fiberglass clamshell design to keep them small. ILM also famously modified a Nikon F3 with a registration pin in the gate and 30’ film back to shoot Vista-format plates inside small miniatures. Some of the other effects houses modified Stein cameras. The Stien cameras were really unique in that they were early stereo cameras from the late 20’s, and they used a unique 8-perf vertical pulldown that stacked two 4-perf frames on top of each other. If you turned that on it’s side… Vista. And then there was the W7. And I mean THE W7, since there was only one. It was built from scratch by Jeff Willliamson of Wilcam, for high-speed work and could crank at 100 FPS, so it worked on every single disaster FX film for two solid decades.

-

Rotary prism cameras in Openheimer

Steve Switaj replied to massimo losito's topic in General Discussion

If you ever get a chance, check out Trinity and Beyond: The Atomic Bomb Movie, by Pete Kuran. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0114728/ I worked with Pete back in the late 90's, he used to own PMP, an effects stage up in the west end of the San Fernando Valley. One day in the late 90's I was shooting miniatures there and he walked out on the stage and started handing out DVD's of his pet project, which was finding and cleaning up archival footage of the atomic tests from the 50's and 60's. Turns out that Pete's dad was also a cameraman, and was involved in the national defense effort filming nuclear tests. It was apparently a big, organized thing that nobody talked about. The Department of Energy leveraged their proximity to Hollywood and maintained a technical facility up in the Cahuenga Pass and employed a small, secret group of working cameramen and technicians to staff it. Pete's dad was one of these guys. Pete says he remembers when he was a kid every once in a while his dad would mysteriously disappear for a couple of days without explanation to a "location project" he would never seem talk about. Pete always thought it was suspicious but only three decades later did he find out that Pop was driving up to Nevada to film big things going boom. Once Pete figured out the story it sparked his interest and he spent years digging around for the old footage of these tests and used downtime at his facility to clean up and remaster the film, eventually releasing it as two CD's He also dug up a lot of really interesting technical information - for example, he found out that Kodak manufactured special film for the bomb test that was kind of like color film, but it was actually three B&W layers that had wildly different ASA's - say 400, 20 and 1. The idea was that as one layer saturated, the next one would be reaching a good exposure window, and by printing it three times with different color filters to pull out the three layers of interest you could effectively get a B&W film with extreme dynamic range - useful for very bright events. -

Apparently, this lens was big with the stop-motion crowd in the 90's I worked on Coraline, and we received a lot of equipment from Nightmare Before Christmas and James and the Giant Peach, and the package included several of these lenses in the older 2-ring style. Apparently the older-school animation setups found them useful for their relatively close focus at telephoto lengths, which played well when compressing forced-perspective sets while still giving the animators some working room. By the time Coraline came around we didn't really use them any more. We were working in 3D, which eliminated forced perspective setups, and by that point we had too much camera motion that would have the game away anyhow. IIRC not a great lens wide open, but it cleaned up pretty well as you stopped it down.

-

I'm not familiar with the Arri S/B's. Where's the power connector? Is it a blind mate to that little metal pin at 7 o'clock on the motor face?

-

Buy some good screwdrivers before you start. You want the type gunsmiths use, with the ground, parallel sides. You can buy the kind with one handle and a set of 1/4" hex tip inserts to save some coin, but you want a set with a good variety of tip widths and thicknesses to choose from. If you use "normal" tapered screwdrivers from the home improvement store - even good ones - the blades will not fully fill the slots side-to-side and top-to-bottom and will concentrate force on 2 points at the top of the slot. Combined with the force need to dislodge some of the old fasteners, you *will* bung up these old, soft, slotted screws.

- 12 replies

-

- 2

-

-

- 16mm

- arriflex st

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with: