-

Posts

1,462 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Posts posted by Carl Looper

-

-

Sensory indistinguishability is a recurrent theme in art and philosophy. The argument goes back to Ancient Greece - if you can't see the difference then what is the difference?

If we reproduce a Chuck Close painting, using photography, we may not be able to see (in the reproduction) the difference between the painting and photography. And we could argue that if we're unable to see the difference between painting and photography, that it therefore doesn't matter which one we use (in terms of the image). Other considerations might then take hold - eg. cost etc.

But the whole point about a Chuck Close painting is that it operates across the boundary between distinguishability and indistinguishability. You can both see and not see the difference.

The same can not be said about the work of Yedlin.

C

-

Here's an example where it could matter what values we're using for shutter and prism loss, and relates to the original post.

Suppose we want to compensate using ASA/ISO. Armed with the values of 135 degrees for the shutter angle, and 25% for the prism loss, we would conclude the total light reaching the film was 56.25% (as calculated above)

With 50 ASA film, we'd then compute the compensation as:

50 ASA x 56.25% = 28.125 ASA

Looking at the available light meter settings (on a digital meter), we'd see 25 ASA or 32 ASA are the available options. And based on what we calculated we might very well choose 25, when we should have chosen 32.

C

-

According to the article, the 130 degree shutter belongs to those cameras which have the published shutter time values of 1/65th (non-reflex) and 1/80th (reflex) at 24fps.

These shutter times are compensation values, ie. to compensate for the non-180 degree shutter angle and (for reflex cameras) the prism. The other way of compensating is to use 180 degrees as the shutter angle (1/48th of a second as the shutter time for 24 fps) and then compensate using aperture or ASA/ISO. The latter is convenient as it means one can read aperture values directly off the meter.

Now lets suppose we did "reckon with" the shutter as 135 degrees, and the prism loss as 25%.

That would mean the shutter admits 135/180 = 75%

And the prism admits the same: 75%

The total amount of light reaching the film would then be: 75% x 75% = 56.25%

The aperture compensation would then be reckoned as:

log2(100%) - log2(56.25%) = 0.83 stops

Now normally (if not invariably) this would hardly matter, as the difference between 0.66 stops and 0.83 stops is only 0.17 of a stop.

But there are situations where it might matter.

C

-

The stop compensation can be reverse engineered from the exposure times given in a bolex manual. If we otherwise assume that 1/80th sec (at 24 fps) is a good enough value, then stop compensation can be reverse engineered from such:

log2(1/48) - log2(1/80) = 0.737 stops

We see that the rule of thumb value of 2/3rds of a stop (0.66 stops) is very close to this computed value.

If we look at all the values provided in the bolex manual for a 130 degree shutter compensation with prism compensation, we see that the compensation value is either 0.781 stops or 0.737 stops, suggesting 0.759 stops might be a good number to use as a more accurate number. If one ever needs such a number.

64 fps: log2(1/128) - log2(1/220) = 0.781 stops

48 fps: log2(1/96) - log2(1/160) = 0.737 stops

32 fps: log2(1/64) - log2(1/110) = 0.781 stops

24 fps: log2(1/48) - log2(1/80) = 0.737 stops

18 fps: log2(1/36) - log2(1/60) = 0.737 stops

16 fps: log2(1/32) - log2(1/55) = 0.781 stops

12 fps: log2(1/24) - log2(1/40) = 0.737 stops

C

-

Here's an interesting post I just came across, giving an account of different shutter angles on different models of Bolex.

http://bolexh16user.net/ExposureAdvice.htm

Of interest to me is a paragraph on "133 degree" shutter models. According to the article, the 133 degree shutter angle is an incorrect shutter angle. It was inferred by a particular author from information in a Bolex manual where an exposure time of 1/65th sec, for 24 fps, was recommended.

In reverse engineering the shutter angle from the exposure time, the author of the 133 value had used the following formula to obtain that shutter angle.

Shutter Angle = (1/65) x (360) / (1/24) = 132.9

In reality (to follow the article) the shutter angle was actually 130 degrees (ie. physically so), and the exposure time of 1/65th sec (given in the manual) was simply a good enough approximation. If we otherwise need the exact exposure time for a 130 degree shutter angle, it can be obtained like this:

T = 130 / 360 x (1/24)

= 0.15046296 sec

which is between 1/66th second and 1/67th of second.

To account for a prism at 24 fps, the exposure time given in a Bolex manual is 1/80th sec (which is another way of "tricking" your light meter into giving you a good aperture setting). Like the 1/65th second value, the 1/80th sec value is probably a "good enough" value as distinct from an exact value.

C

-

I recently shot some 100 ASA 16mm film without any light meter at all, for the simple reason that on the day of the shoot, my 25 year old digital light meter finally kicked the bucket. I had to guess the f/stop. Surprisingly the results were quite okay. So along with stuff I've done without a viewfinder, I can add "without a light meter" to my list of achievements.

It is generally accepted that 2/3rds a stop (0.66 stops) compensation is required for the Rex Bolex, to compensate for the odd shutter angle and the prism. There are a number of reasons for accepting this, and the principle one is that filmmakers using this rule of thumb get good results.Using this information, along with knowledge of the shutter angle, we can (out of pure curiosity) calculate the percentage of light lost to the viewfinder (by the prism).The literature suggests a fully open shutter angle on the Rex Bolex is 133 degrees or 135 degrees. We'll use both values in our calculation.The light admitted by the shutter (compared to a 180 degree shutter) can be calculated like this:

133 / 180 = 0.7388' (73.88 %)

135 / 180 = 0.75 (75.0 %)A nice round result of 75% may very well indicate that such a value is a "rule of thumb" value rather than an actual value, but in any case we'll work with both values and use the difference in stops to estimate whether the difference matters.Now if the Bolex did not have a prism, the required compensation in stops (for the shutter only) can be calculated like this:133 degree shutter: log2(1) - log2(0.7388') = 0.4365 stops

135 degree shutter: log2(1) - log2(0.75) = 0.4150 stopsWe can see the difference in stops between the two shutter angles is negligible: 0.0215 stops.In any case, assuming the full compensation for a Rex bolex is 0.66' stops (2/3rds of a stop), then the light lost to the viewfinder, in stops, would have to be:total compensation - shutter compensation = prism compensation

133 degree shutter: 0.66' stops - 0.4365 stops = 0.23 stops (prism loss)

135 degree shutter: 0.66' stops - 0.4150 stops = 0.252 stops (prism loss)Converting such back into fractions/percentages, we get (if I'm not mistaken):1 - (2 ^ -0.23) = 100% - 85.3% = 14.7 % lost

1 - (2 ^ -0.252) = 100% - 84% = 16 % lostBut as a check for errors lets perform the forward calculation where we should get 2/3rds of stop as a result (for both shutter angles). We compute the amount of light that reaches the film with:shutter admission x prism admission

for 133 degree shutter: 73.88% x 85.3% = 63%

for 135 degree shutter: 75% x 84% = 63%So far so good. Converting such to stops we should then obtain the original rule of thumb (2/3rds of a stop).log2(100) - log2(63)

= 6.6438 - 5.9773

= 0.6665 stops (2/3rds of a stop)Assuming there is no error in this calculation (based on the check), and that 2/3rds of a stop is correct (based on experience), and that the shutter angle is 133 degrees or 135 degrees (based on how could this be wrong), then the light lost to the viewfinder must be in a ballpark of:14.7%

16%Or to put it another way (on the same assumptions), were the prism to divert more than this, then the required compensation in stops would need to be more than 2/3rds of a stop.C -

I find DIY scanning (or indeed optical printing) is a lot of fun. I'm onto something like a tenth iteration of a DIY scanner/printer. I find DIY work (on any level) is very much part of what experimental film making is all about. Making stuff in all the odd ways one might imagine. And when you make a mistake (so called) the important thing is that it's yours and not someone elses, and therefore something you can do something about - or indeed choose not to do so. For you have that choice. A so called mistake can become a feature of a work instead. You get to decide. And either way it becomes a real thing when you do it yourself.

C

-

Ah yes. It would be quite difficult, if not impossible, to get a quality off-the-shelf sensor module in there as a substitute for the ground glass screen. The ground glass provides for more flexibility in sensor options. David's design graphic is beautiful.

C

-

A flicker free viewfinder is not out of the question in such a system (and perhaps it's just a question of a software update). The flicker is only there because the viewfinder display is being continuously updated. Were it to otherwise update itself only when an image is available (in phase with the shutter), it would then not exhibit any flicker. Not that it actually matters in any way. And indeed the flicker can be regarded as a reminder that the viewfinder image is just a viewfinder image.

C

-

In the Logmar camera the viewfinder image is by means of a second internal lens imaging a ground glass screen. I don't know if this is the same for the Kodak camera. Ideally (from a user experience point of view) you would not have a ground glass screen at all and simply have a lensless sensor of the appropriate physical size in place of the ground glass screen. Either way I suspect the Kodak camera uses a higher definition sensor to facilitate it's viewfinder image.

C

-

There is a short section in the video where they are shining a light through the gate while the shutter is going, in an effort to demonstrate there is nothing between the light and film, ie. that the camera uses a mirror shutter (or oscillating mirror) to facilitate the viewfinder image.

The Logmar uses a similar design, with a flickering viewfinder for the same reason. When the shutter is not spinning the image does not flicker. When the shutter is going slowly the flicker goes slowly.

Note that the visible flicker we see in the video may additionally be due to interference between the video camera shooting the scene and the Super8 cameras viewfinder image. But the flicker of which I speak is not this potential source of interference but that to which the commentator refers, which you can see in the difference between when the shutter is going and when it is otherwise stopped.

C

-

The flickering viewfinder demonstrates that the viewfinder is thankfully being driven by a mirror shutter, rather than a prism. If the viewfinder image were otherwise derived by means of a prism you'd then need your film exposing lenses to be specifically designed to accommodate for that viewfinder prism. A viewfinder image derived through a mirror shutter means generic lenses can be used with the camera.

C

-

Carl this looks like a big camera size wise ?

Makes my beloved Leicina Special look even more special in that nice German kind of way .

Yes, they are quite large in size. Not as large as the Logmar but still larger than your traditional Super8 camera. And yes, the Leicina Specials remain quite special. I have two of them!

C

-

Here is a more compelling video of the camera at CES, complete with shots of lenses.

C

-

The Logmar was sold without a lens. In preparation for purchase of that camera I acquired a Schneider-Kreuznach 1,8 / 6 - 66, from ebay.

You can still get these lenses (and other versions of such) on ebay. Some of these lenses even sell with a camera attached to them.

C

-

All fine, let us put technics aside. We have reached, I think, an interesting point of the discussion that begins with early perspective drawing in the Renaissance. Now that Rochester has picked up the Renaissance, speaks of an analog renaissance (which in my humble opinion is plain Schrott) we are merely forced to it. After the draughtsman who sits behind or over a tense parchment we have seen the view box with the photographic chamber again. The photographer deals with an image upside down and inverted sideways (unless he adds a loupe).

Cinematographers like the Lumière operators dealt with the same situation, only that the image was less than an inch wide, on the film itself. One can refine one’s skills in that with a Pathé industriel, most probably the last Kine camera to allow direct framing and focusing on the raw stock. One could place a ground glass in the aperture as well, a loupe remains indispensable. The Le Blay of 1930 offered a behind-the-film prism, the Hodres camera of 1935 had a viewing tube pushed up to a pressure frame, and some more designs provided for the archaic method. Then came the rackover systems and the reflex viewfinders. Le Prince’ 1888 camera has two identical lenses one above the other. The upper one projects an image on a ground glass, both lenses rack forth and back together by action of a lever.

There was no such thing as a consumer movie camera without an optical finder until now. All of a sudden comes a conglomerate of a movement around the more than 50 years old Super-8 Instapak Cartridge, driven by a crystal controlled electric motor such as is known from professional cameras, plus electronics out the realm of industrial image processing and palm computers. Whoa. And no eyepiece, no ocular, no. We are being placed back rearward, onto a distance for comfortable observation of a gleaming screen. This is 21st century with 19th century photochemistry and mechanics glued under. It’s cell phone physiology alongside colour negative exposure. Or Ektachrome. Or TXR.

I herewith declare that I have the deeply engrained habit of peeping through finders, of putting my skull and an eyepiece cushion in contact, of eliminating ambient light from my view. I am not one of the proclaimed next generation, inspired by a camera. Have the Paillard-Bolex cameras that I use ever fuelled my creativity in any way? Must find out. Was it one of the Bell & Howell? The Moviecam? That, that is total tat.

Yet one advantage can’t be denied. It’s parallax free. Yep.

Can anybody tell the opening angle with the revolving shutter? The exact exposure time per frame at, say, 24 fps? Is it a revolving shutter or an oscillating one?

Yes, the use of the term "renaissance" in Kodak propaganda is really quite grating given history proper.

The history of cameras is a long one. Indeed cameras go back much further than the Renaissance. The meaning of the Renaissance will be of a revival as much as a renewal. It will be out of a renewed interest in the ancients. A picking up where ancient thought had left off. A getting back to work after centuries of neglect. Cameras and optics - these will not be invented or discovered during the Renaissance, but rediscovered. Reinvented. For what will be different is an enthusiasm for it. Where such knowledge had otherwise languished in books, speaking of a bygone era, to be taken as gospel or heretical depending on the material and your point of view, it would spill out into the streets, into the world at large, and become inspiration for it's evolution. No longer frozen. The beginning of modernism.

Postmodernism becomes the more difficult to theorise.

C

-

Right, but how do you get focus with a standard definition monitor on a little LCD panel in the bright sunlight of the day?

Digital cameras are nearly impossible to find focus, without focus "aids" of some kind, none of which exist on a film camera.

Yes, that's very true. A zoom lens proves quite useful. Zoom in. Focus. Zoom out.

Another technique involves rocking the focus ring back and forth around the uncertain point. One obtains an understanding of where the focus must be given where it isn't. A bracketing in on where it must be. The sought after focus will be at the bottom of that valley between one direction of the ring and the reverse. One approaches it from one side and then from the other, in rapid succession, back and forth, encoding where it must be in the movement of one's hands, reducing the span of that movement until there isn't any. The in-focus becomes necessarily there by virtue of the out-of-the-focus either side of it. It is how otherwise automatic focus systems work.

If the Logmar viewfinder (or any viewfinder) has an undeniable purpose, it will be for framing/composition.

C

-

I inadvertently obtained an Ektachrome look when I was writing software to correct for the orange mask in scanned neg. I didn't realise it at the time.

The software I wrote was written under the mistaken impression that the orange mask in negative film is something to be removed after scanning negative film. But in fact the mask itself is not to be removed. It is only the orange bias that needs to be removed (be it by software means, or otherwise using filters or light). But if you otherwise remove the mask (in addition to removing the orange bias) you will transform the result into that which colour reversal obtains. And that is what I ended up inadvertently writing. I was doing the opposite of what I thought I was doing.

So if anyone needs to know how to obtain a colour reversal look from scanned neg I have the answer!

Carl

-

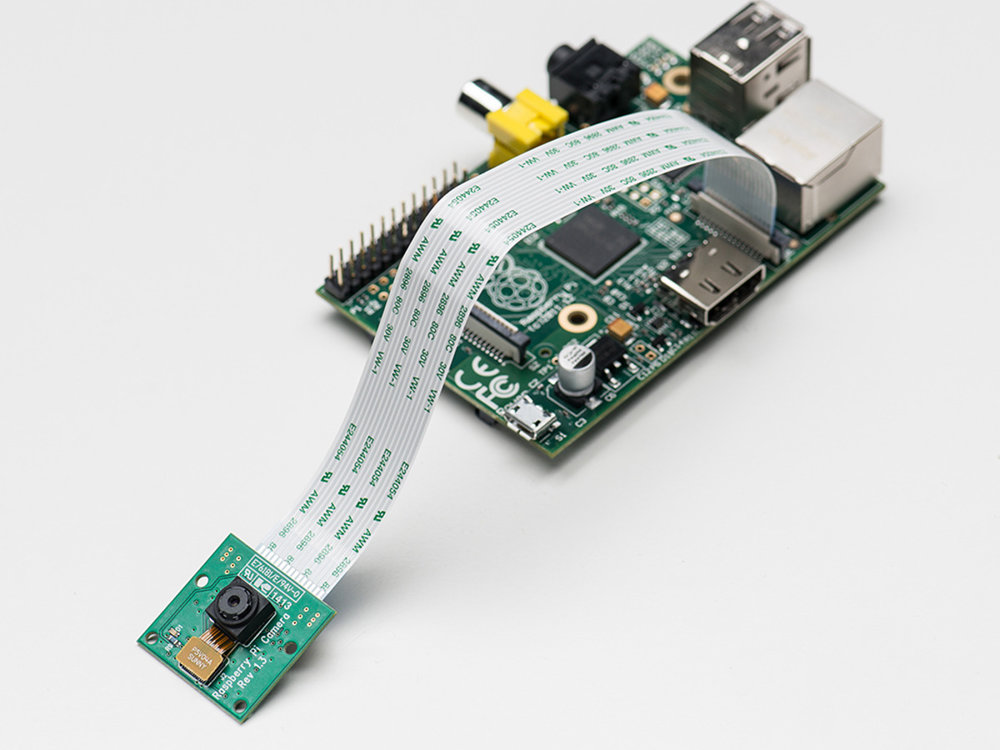

If one were to otherwise use a naked sensor in place of the ground glass screen, it would have to be a sensor that is physically larger than the size of a Super8 frame of film. And this could very well be expensive. If otherwise using a cheaper sensor it may not be large enough. For example a $25 Sony sensor I'm looking at has a size of 3.76 × 2.74 mm, so as a substitute for a ground glass screen it wouldn't work. The image falling onto the sensor would be larger than the sensor. The sensor would be looking at a very cropped version of what the film otherwise sees.

But if I otherwise put a small lens on this cheap sensor, I'd have a small camera I can point at a ground glass screen, and get a perfectly adequate 3280 × 2464 pixel image of that which is otherwise projected onto the ground glass screen by the main camera.

-

These photons landing on the ground glass forming an image, are the most direct connection available between subject and photographer while using a camera. A monitor is incomparably less. A sensor effectivly counts photons and this data is manipulated to make an image that the eye might accept, then offered to the monitor.

The very fact that there is any confusionn between the relative value of these two viewing options for the photographer is, sad to me.

Even some cinematographers, forced by our momentary perch within history, to use digital aquisition, will choose an Alexa with an optical viewing system. I salute those guys. Their instinct or intuition for what is valuable has somehow remained intact.....

Surely the most direct connection between photographer and subject is not when your head is attached to the camera but when otherwise looking at the subject with your own eyes. That said, I'd suggest this direct connection is not what one is after in cinematography (or photography). But nor is it one to be found inside the camera

I'd argue the real connection being sought, or created, is not that created in our eyes, or in a camera, or indeed on the film. It is that connection being created during a screening of the completed work. That is how I understand it. When making a film one is really making that which happens during a screening before an audience - in the eyes and mind of the audience, which includes ourselves as part of that audience.

During production, our own eyes, be it looking directly at a scene, or through a viewfinder, merely provide a kind of preview. A simulation of what one is after. A visualisation of that which isn't really there until the work is up there on a screen in front of an audience. Our eyes, be it directly, or through a viewfinder, become a means to an end, rather than an end in themselves.

C

-

Seems that we talk at cross-purposes. I am perfectly aware of viewfinder systems and their function. My question was why should one build in a ground glass or any other frosted or matted surface for an image to form upon when a sensor cannot see it. We would have to install a lens between GG and sensor to project the image there. Besides loss of light in the ground surface one had the advantage of more space available when the sensor can be set up at a longer distance.

Yes, I know you understand all of this (from previous discussions) so I'm quite perplexed what you are otherwise trying to suggest.

If the sensor could not see the ground glass screen there would be no image on the LCD screen. The sensor is able to see the ground glass screen by means of second lens between the ground glass screen and the sensor.

Personally I would have designed the Logmar without a ground glass screen, and have simply put a naked sensor (without a secondary lens) in the same plane as that which the ground glass screen otherwise occupies. But perhaps it was more convenient or cheaper to do it in the way that Logmar did.

The third alternative is to have the ground glass screen and an eyepiece (instead of a video camera) trained on such, as in traditional designs.

A benefit of a video camera (and LCD screen) is the way it facilitates decoupling of the cinematographer's head from the camera. One can move a camera around without the added inconvenience of requiring one's head attached to the camera.

C

-

Thank you, Carl, for the explanation. I must say that I’m having some difficulty accepting this as true. A ground glass is an aid to the eye, an image sensor wouldn’t need one, would it?

The ground glass screen (in any camera) isn't really an aid to the eye, unless by that we mean an aid to focus. The ground glass screen is the same distance (or effective distance) from the lens as the film is from the lens. Or at least we would want to it to be. It means if an image comes into focus on the ground glass screen, we can be satisfied it must also be in focus on the film. If the image were otherwise projected directly into our eyes, we can't be convinced the image on the film is also in focus, because our eyes can bring an otherwise out of focus image back into focus.

The same principle operates in the Logmar camera. Now an alternative to using a ground glass screen (and an internal lens/sensor trained on such), might have been to have a naked sensor in place of the ground glass screen, with the image falling directly onto the sensor. It would have done the same job as a ground glass screen, and provided a much better looking image to the LCD, ie. better user experience. However this is of secondary concern. The most important purpose of a viewfinder is to provide visual feedback for framing (composition) and focus. And the ground glass screen, with secondary lens and sensor on such, pragmatically provides for that.

C

-

Yes, the Logmar was designed with a port at the top of the chassis for any future magazine that might like to be invented for it.

C

-

What hardly anyone notes: How does one project her/his film from behind the Max-8 aperture without image loss? Is there a corresponding projector available? No, there isn’t.

Most people scan Super8 neg to digital rather than making prints. And a digital scan makes the most of the additional exposure provided by the Max8 aperture. Indeed it is transfers to digital/video that inspired Max8 mods in the first place.

Of course, with the promise to bring back reversal, Super8 film could very well be back in film projectors again, where it would be back to 4:3 framing. Don't know if it is the same on the Kodak camera, but on the Logmar viewfinder you can choose between 4:3 and Max8 frame guides.

And there's nothing to stop anyone modding a projector for Max8. Plenty of cameras have been.

C

Could Digital Kill Film?

in General Discussion

Posted

The point of the analogy is that while it's certainly possible to make two materially different images indistinguishable, there is an assumption that such should be pursued. If I mention Chuck Close it is merely as an example of where this is not the case. In the work of Chuck Close there is both an aspect of the work which is quasi-independent of the materials involved, and which passes from one material to another, from photographic materials (be they analog or digital) to paint, and back again (eg. in a catalogue or a website). And there is another aspect of the work which is not independent of the materials and is very much situated within it.

And as a witness to such work one can see (ie. with one's eyes) both of these aspects at work. They play off each other.

Now it doesn't matter whether one likes the work of Close or not. We can still appreciate the absurdity of any suggestion that Chuck Close should give up his paintbrushes, and take up photography instead.

C