-

Posts

521 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Everything posted by Frank Wylie

-

intermittent overexpose of frames on 16mm footage

Frank Wylie replied to Habib Beh's topic in General Discussion

No chance this was home processed in a Lomo tank? -

16mm sprocket caps to fit on Oxberry shuttle

Frank Wylie replied to Patrick Beveridge's topic in Cine Marketplace

PM me with your email. I need to take care of some business right now, but will answer when I can. Thanks Frank -

16mm sprocket caps to fit on Oxberry shuttle

Frank Wylie replied to Patrick Beveridge's topic in Cine Marketplace

Better check that gate: I don't remember if the projector gates will fit in the camera and vice-versa. The fork offset might prevent it from working, but I get confused between ACME and Oxberry offsets... The picture is what I have for 16mm... -

16mm sprocket caps to fit on Oxberry shuttle

Frank Wylie replied to Patrick Beveridge's topic in Cine Marketplace

If so, I can't help you. I have a set of 16mm and 35mm gates with matching feed rollers for the projector head of an optical printer, but nothing for the camera. (Heck, I even have the chassis of the projector head for it all to fit into, along with take-up torque motors and some odds and ends like the old gate micrometers) Sounds like an animation camera you are trying to get back into service. Right? -

16mm sprocket caps to fit on Oxberry shuttle

Frank Wylie replied to Patrick Beveridge's topic in Cine Marketplace

This is for the camera, I assume; not the projector head, right? -

16mm sprocket caps to fit on Oxberry shuttle

Frank Wylie replied to Patrick Beveridge's topic in Cine Marketplace

"Sprocket Cap"? Please explain... I have a 16mm Oxberry Gate and I don't know of what you speak... -

intermittent overexpose of frames on 16mm footage

Frank Wylie replied to Habib Beh's topic in General Discussion

OH, buy the way.... what model B&H camera do you have? :unsure: I was assuming a DR 70 or variant ... -

intermittent overexpose of frames on 16mm footage

Frank Wylie replied to Habib Beh's topic in General Discussion

Sounds like your spring motor is sticky and is not releasing smoothly. The spring lubrication gets sticky and as it unwinds, it will create sudden bursts of speed as the grease unsticks. You need to have it cleaned or try another camera. You weren't hand cranking it via the accessory drive at the base of the camera, were you? You were using the ratchet spring motor, correct? -

David, I wasn't trying to single anyone out and I apologize if it appears that I did... I agree that Super 8mm would probably not be a good medium to simulate a motion picture from the silent era. "The General" is a pretty late era Silent Film that had much of the nascent technology that would very soon be pressed into Sound Film Production. Again,as you state, it is very difficult to generalize (pun not intended) about Silent Film technique without specifying an epoch, genre and even nationality you are trying to emulate. There are as many examples of deep focus cinematographic shots as there are selective focus shots throughout Silent Film History. Here are some films I have timed that are worth watching for amazing cinematography: "Hotel Imperial" (1927) Bert Glennon "Intolerance" (1916) G. W. Bitzer "Corporal Kate (1926) Henry Cronjager - wild process shots! "The Wedding March" (1926) Roy H. Klaffki and Ray Rennahan (wild diffusion and technicolor sequences) "Safety Last" (1923) Walter Lunden There are many more I can't think of at the moment, (I estimate I have timed about 200- 250 silent films) but unfortunately few are available on DVD and can only be seen through the 35mm print loan program of the Library of Congress. Many are very obscure by their very nature and a lot are heavily damaged and incomplete but the sheer variety of cinematographic styles represented is staggering.

-

So many people today have a hard time wrapping their heads around how Silent Film Makers uses such slow film stock and got acceptable depth of field because of several factors: So many faulty assumptions are based upon our current understanding of how to process film by time, temperature, set gamma and aim points. That did not exist in the silent era, period. Go back and look; Jones and Crabtree didn't start codifying SMPTE processing standards until well into the late 1920's. Depending upon the era, the rawstock was largely blue sensitive and was processed shot by shot by the cinematographer himself by direct inspection. Light meters and development to time/temperature only became dominant when the sound track demanded a consistent result to remain audible. The use of arc light and Hewitt-Cooper Lights (more or less mercury vapor jacked-up to extreme) lights allowed mid-aperture exposure on lenses easily on sets. Most cameras had an integral punch and each shot was punched at the head and tails of the scene so it could be processed by hand, by inspection and in what strength/type developer the cinematographer deemed proper. The concept of "pushing" or "pulling" a scene was just a normal part of processing, not a deviation from "normal". Clarence Brown even had a way to "dodge and burn" release prints by hand and did it on the first release of "Intolerance". Their World and ours is not the same. We don't work with their tools because we are so separated from the medium by the light meter and standardized film processing. It was an art because it was a CRAFT. We don't do craft anymore... (edit) I don't mean any disrespect to the masters of cinematography in post silent era; I just want to draw a distinction between how silent era cinematographers were both cursed and blessed by being unbound from any set standard other than it should meet their artistic vision. I really shouldn't say we don't do craft anymore, but should say we don't do craft the same way...

-

These are exceeding rare laboratory grade Super 8mm film cartridge opening machines! If you've ever tried to open a Super 8mm Cartridge gently when processing your own, you know what an ordeal it can be! If you have a dozen or more to open, it can be torture on you and possibly your film. This machine, which is about 10 lbs of cast aluminum, has a razor sharp blade on a circular bit under the cover. Place the Super 8mm cartridge in the aperture, close the lid, give it one revolution on the handle and you have a perfectly cut circle in the side of the cartridge to gently extract your film! Fantastic shape! Almost like new! $250 USD (willing to entertain offers as well) to me via Paypal or USPS Money Order + actual shipping cost to you. Made by Kodak for Kodak Super 8mm cartridges; what more can you ask for? Thanks for looking!

-

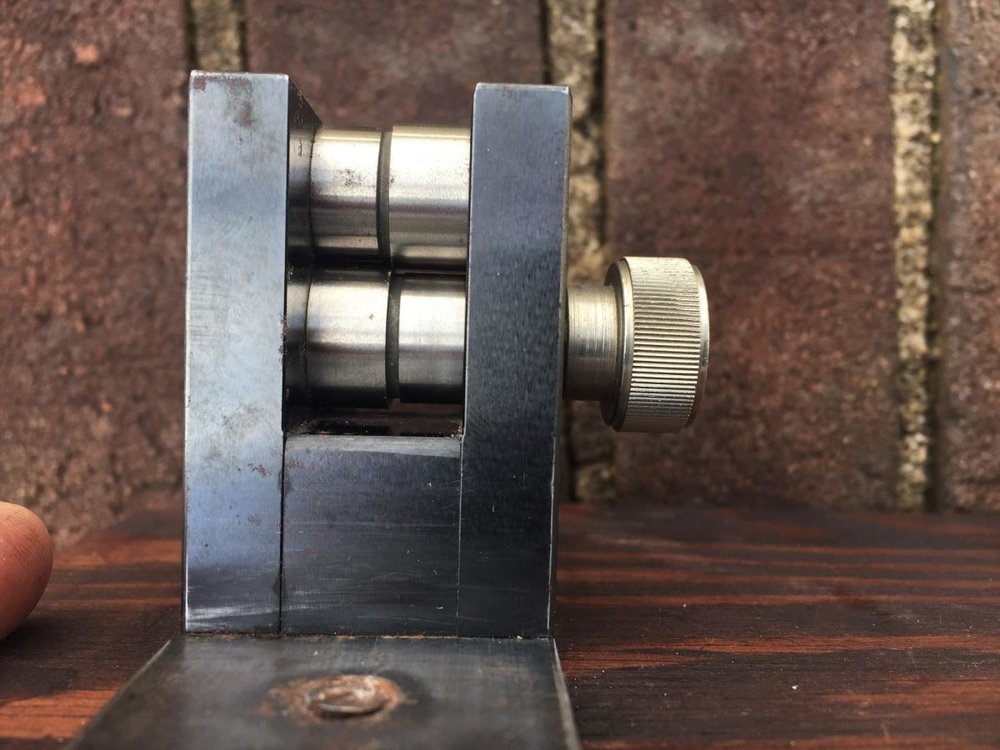

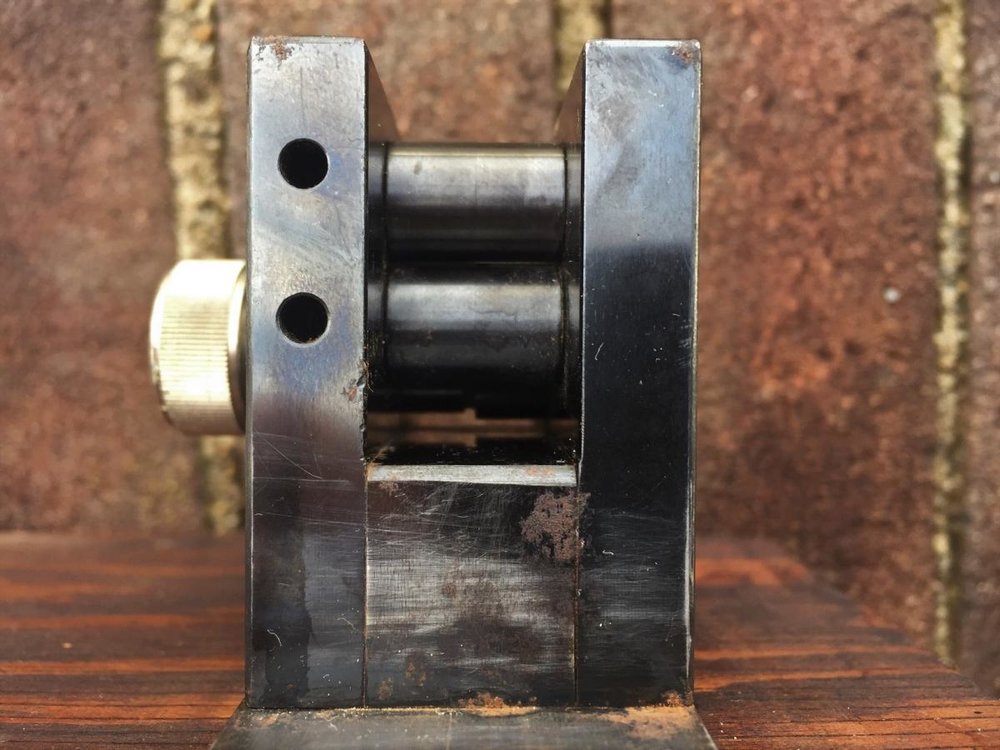

Professional Grade Film Slitter. Designed to fit between film rewinds and slit Dual 8mm film to 2x single strands after processing. No makers mark I can find, but it came with a group of Peterson Printer spares about 20 years ago, so it might be a Peterson. The cutters are precision machined stainless steel, the shafts all sit in ball bearings, the remainder is mild steel with bluing like Oxberry/Acme gates, so it is a very well built machine. There is a bit of surface rust on some areas but a quick hit with crocus cloth or very fine metal sandpaper should clean it up nicely. I'll let the buyer do that to avoid sanding areas they might not like... I see very makeshift film slitters going on Ebay for up to $200 USD, so my asking price of $250 USD plus actual shipping cost to you should be fair, but I am willing to entertain offers. First come, first serve. I take Paypal and USPS Money Orders ONLY. Posted on other sites, so prior sale is always possible.

-

Colormaster 2000 35mm Prismatic Analyser

Frank Wylie replied to Frank Wylie's topic in Post Production

Mark, It is a refurbished unit, but it was probably originally built about 2000 or so and appears to have been hardly used by the pattern of wear on the machine. The HFC 300D, which was essentially a Hazeltine with some updated circuitry, was built up until about 2005, but Hollywood Film Company reorganized just about that time and is essentially a film storage company now. We bought the last two units ever made from HFC in 2007 (new old stock) and had them serviced up till last year by their former repair tech, but he was unable to get the required spare parts to continue to repair the 300D, so we had to retire one of the machines. The Hazeline was based on flying spot technology with circuits using up to 50K volts and no one makes high voltage components anymore; at least the ones we needed. The Colormaster is based on a PAL CCD camera with LUTs for film stock emulation. Media Migration Technology (MMT) is the successor to RTI which went insolvent and was liquidated, https://mmtfilm.com/products RTI had absorbed and consolidated companies like Lipsner Smith, BHP (Bell and Howell Panel Printers), FilmLab (of the UK and Aus.), Triese Engineering and Caulder (film processors). A few of the former management and workers of RTI formed MMT and are trying to carry on the best they can with the ever shrinking market; mainly archival work. Yes, it is a Steenbeck controller! It's weird running it with my left hand, but better than other controllers they might have pressed into service.- 7 replies

-

- 1

-

-

- Film Timing

- Film Grading

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Colormaster 2000 35mm Prismatic Analyser

Frank Wylie replied to Frank Wylie's topic in Post Production

Phil, You are right; I don't know of any analyzer ever built that would reproduce exactly the color and contrast of a final film print, but it's probably one of the most flexible systems ever built in simulating a good approximation of what the end result could be of a film print. That has always been what a good timer does; they extrapolate how the image WILL look from what they see on the screen. You can only develop this skill through experience with the grading machine and with the historical characteristics of the output of your film processing workflows and stocks. Our work is to preserve and protect the collections of the U.S. Library of Congress, Motion Picture, Broadcast and Recorded Sound Division. The vast majority of these collections are Nitrate 35mm Motion Picture elements deposited at the Library through a staggeringly complex series of agreements with such depositors as The American Film Institute, Major U.S. Motion Picture Studios, Corporate Institutions, Private Donors and the U.S. Copyright Division. Our collections are much more diverse than listed above, but you get the general idea... Our photo chemical lab is strictly monochrome (B&W), but we do have 4K digital workflows for color work (which I won't address now). A typical job would entail preserving a B&W 35mm feature from the 1920's. Assuming we have the original negative in our vaults, it would be sent to the lab for inspection and hand repairs of the element; inspecting for damage, shrinkage and other potential problems in duplication. Once repaired and prepped for timing, I would time the element and then note any problematic aspects of the element and chose the proper motion picture printing machine upon which to generate an archival interpositive and, if in good enough shape, a reference print directly from the nitrate negative. If it is in poor condition, the interpositive would then be used to generate a dupe negative, which would then be timed and printed to make a reference print for projection. That's a grossly simplified workflow, but encompasses the basics. If the element has sound, is a projection positive with color tints or tones, non-standard perforations or any other myriad variations on what we can have on hand, the process becomes quite complex very quickly. The Colormaster will mainly be used to time new positive prints from our newly generated duplicate negatives. I will still have to time interpositive elements to make dupe negatives by eye, but this helps considerably in reducing eye strain by off loading the timing/grading process of positives from archival dupe negatives!- 7 replies

-

- Film Timing

- Film Grading

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Thought a few of you might be interested in my new toy at work; A 35mm Colormaster Prismatic Analyser. Just spent the last 3 hectic days assisting Media Migration Technology (formerly RTI) install our new system. It replaces one of our HFC 300D Hazeltine analyzers that was inoperative and allows me to return to electronic grading of negatives instead of grading them by eye over a light table.

- 7 replies

-

- 3

-

-

- Film Timing

- Film Grading

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

I understand. I have a friend who shot his first feature on the new Red One. It was an adventure, for sure! Seemed like every day he had a firmware update sent to him by the manufacturer for a problem discovered the day before! Don't think you get quite that level of service anymore, but similar problems remain with modern generation digital cameras.

-

I understand about the issues of money; never had a lot of it myself and never worked on a production dripping with it either, but I always saw to it the basics were tested somehow. You can easily perform a basic film camera test with about 100 feet of a 400 foot magazine of any type of motion picture film; registration, focus, basic exposure, scratch, etc. Clip the last 5 feet off (in the dark of course) and retain it to compare with the processed film to double check the lab for processing scratches. No need to blow an entire magazine of film as long as you have a darkroom or changing bag on hand.

-

Film or Digital, I cannot IMAGINE embarking on a project without shooting comprehensive camera and film stock/digital media tests PRIOR to shooting! Am I just an old fossil and out of touch? I just don't get it... When you can't afford to test, you surely can't afford to re-shoot the entire project; so it doesn't make sense, now does it?

-

It might just need a good cleaning of the gate and to re-tension the lateral springs; especially important for Super 16mm cameras. I don't work on them, but the other two responders on this thread do; you might want to talk to them... Wish I could have been more help!

-

I would STILL like to know if it was fresh film stock. Is this the first time you shot with the camera?

-

Yes, I looked at the pics of the pressure pad and gate. The pad appears to have some wear on it; nothing too dramatic that I can tell, but it's hard to tell what might be a defect. Where are the tiny marks you speak of? Are they on the edges of the pressure pad? Was this new film stock? If not, how old was the film? IF the film was tacky when going through the gate, it could have "cocked-around" a tiny bit, sticking and freeing itself as it went. The shots inside the camera body look like there is some emulsion dust around the gate; do you have the film itself and can you look at the base and emulsion to see if there are marks or scratches?

-

I think it can be stabilized electronically with After Effects or DaVinci Resolve, regardless of what caused it. This, of course, would be a problem if you want to go the traditional route of film to film...

-

Just a sec. that might not be true...

-

If you look at the transfer you have, you can see the outline of half of the perforation on the top and half of it on the bottom. These perforations are very steady as far as I can tell, so something has to be moving around IN FRONT of the gate; not the film jumping around in the gate.

-

Are shooting "normally"? No mirrors? Is the lens secure on the camera?