-

Posts

1,462 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Everything posted by Carl Looper

-

I have a Logmar Super8 camera, and the mirror shutter design was discussed during development of the camera. The mirror shutter deflects the image to a ground glass screen where it is picked up by a video camera and delivered to the LCD. This design allows the most amount of light to find the film. If running the camera at a slow frame rate, one will find the LCD image flickers. I have no information on the relationship between Logmar and Rochester, or any idea on the Kodak camera design, but we need not assume from the LCD that the camera uses a prism. C

-

Yes, $2 million is lot to pay for a Super8 camera. If they could bring it down to $2000 that would be better. :)

-

The Logmar camera has an LCD screen, but it doesn't use a prism. It obtains it's image by means of a mirror on the shutter. So I imagine this Kodak camera might do the same.

-

I had a contact print done in the late eighties, of a Super8 film I had made. Originally shot on Kodachrome 40. The print was superb. I was very surprised at the time. They managed to get the contrast exactly right (pre-flashing the film?) and there was only a very slight increase in grain. I still have the original film, and my co-producer has the print, which he screens every now and then. C

-

$2000 is is a realistic price That's the equivalent of about $650 in 1980, or $525 in 1978. I recall spending at least twice that on a Super8 camera back in the late seventies, early eighties. C

-

The lateral perf movement problem in scans of Super8 is a problem with scanners - not with Super8 film. Look at a Super8 camera gate, and a Super8 projector gate. On one side of the gate is a hard edge guide. And on the other side of the gate is a spring edge guide. It is these edge guides that control where the film is located during camera exposure and subsequent projection. It has always been this way. The perf plays no role whatsoever in the lateral positioning of the film. No role whatsoever. But if a scanner otherwise uses the perf for this purpose (to control the lateral position of the image) it will result in the observed effect (or defect): the image will jitter laterally. In other words, any sideways jitter, in scans of Super8 film, is an error the scanner makes. When a scanner is modified to use the edge of the film (rather than the perf) this modification is not making any correction to an error in Super8 film. It is making a correction to what was an error in the scanner. C

-

Yay.

-

Scanners which otherwise use a perf for both vertical and the horizontal registration are effectively implementing a "square claw" that fits a perf exactly. And that is an error. But it is an error the scanner introduces. It is not an error a camera introduces. Basically, a camera is designed to handle the film mechanically (for obvious reasons) and the mechanical design is such that it allows for variation in the film perfing and the film width, in the way previously described - and in such a way that preserves registration (the ability of a projector to reconstruct the camera). It simply requires a projector to work in the same way as a camera - decoupling the vertical and horizontal registration: where the perfs provide only for vertical rego, and the edge guides provide for horizontal rego. The correction made to scanners in recent times (to use the film edge for horizontal rego, rather than a perf) is a correction to an error in scanner designs - it is not a correction to some assumed error in the camera (or film) design. C

-

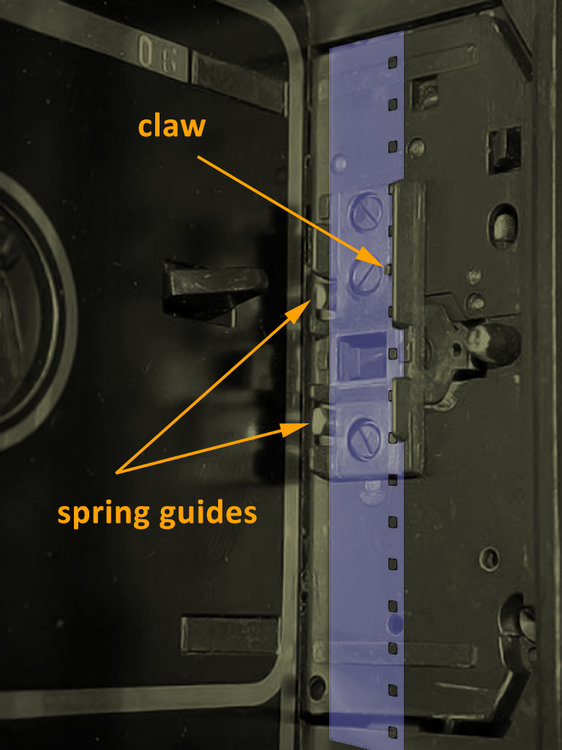

Hi Tyler, the claw is not square. It is very much thinner than the perf. It is tapered, and it has an arcing motion. If the claw were otherwise almost fitting the perf exactly, any sideways variation in film perfing (as exists in reality) would result in the claw hitting the film, rather than entering the perf. In other words the Super8 claw/perf relationship is designed for pull down only (and providing vertical registration). As it should - as this allows for any sideways variation in the film perfing. It is the edge guides (not the claw) which provide for sideways registration: a hard edge on one side (the perf side) and a spring edge on the other. The spring edge allows for variation in film width. C

-

In the early days of Kodak i understand that they started out targeting an existing but very small market of commercial photographers, but they then made the decision that there was a much bigger market to be tapped - to sell film to everyone - not just the big end of town but also the so called "amateur". Professional photographers became quite pissed off with this idea. They figured if anyone could take a photograph who would need a professional? It is around this time that the term "amateur" changed it's meaning from someone held in high regard due to their love and knowledge of a particular field (such as photography) to someone to be treated as incompetent in the field. Likewise the term "professional" changed it's meaning from not just someone who earned their living from their work, but someone who did such work the "right way". Echoes of this history reverberate to this day. For example, one might hear someone suggest that shooting something in a particular way (eg. in shallow focus) is a "professional" way to do a shot. C

-

Hi Tyler, I'm not quite sure what you are describing but the Super8 claw is pulling the film down in the way you have otherwise described. It engages the bottom edge of the perf and pulls the film down (or pushes it down depending on your point of view). The claw action provides for vertical (up/down) registration. The edge guide on the perf side, (and the spring guides on the opposite side) provide for horizontal (sideways) registration. C

-

Here is a diagram of a Super8 camera gate. Note that the claw used to position the film for exposure is using a perf a couple of frames above where the image is otherwise exposed.

-

In the following diagram, the perf marked B is the perf used by the claw in Super8 cameras to position the frame marked A. So to get a good register on scans of Super8 film would require that a scanner use perf B for registration of frame A. In a larger format, such as 16mm, the vertical jitter that would otherwise result by not using the camera's claw perf would be a lot smaller so it's not as necessary to attend to such details. But with Super8, being a smaller format, it requires more attention to such details (if we want to remove the jitter otherwise caused by using the incorrect perf). Most scanners can't do this yet, but it would be a good thing if and when they can. Until then, image based stabilisation will remain the perfectly acceptable alternative. Note. The following is a composite image assembled from individual scans with perfs added in where they were otherwise missing in the source. It is for explanatory purposes only.

-

I took one of the shots from the sample and re-stabilised it.

-

I downloaded the sample and did a quick stabilisation in After Effects (using motion trackers rather than warp stabilise), and a quick Auto levels on it, and the result looks great. Will post a vimeo link when it's ready. C

-

That's very true. But not everyone has a second hand Super8 camera sitting in their cupboard, or want to gamble on a second hand camera off ebay. Certainly the new camera is of interest to the existing film community, but consistent with a 100 years of Kodak marketing, their audience is not just the existing professional, but more so: anyone who wants to play. C

-

I quite like the fact the sample didn't go down the road of an overblown marketing sell with obsessive production values. The sample takes a different route. It says: "here is a test" rather than "here is an advert". It's a way of involving the community with an ongoing process. If we can recognise what it might otherwise lack, we can also recognise what we might otherwise do if we had the camera. C

-

The posted sample looks great. Re. stabilisation If we exposed the same film stock in a brand new top range 1970s Super8 camera (hypothetically speaking) and put the results through exactly the same scanner and post stabilisation process, the results would be exactly the same as that which is posted (I'd suggest). in other words the camera is not the issue. In the scan one would see the same rocking. It's just due to the scanner not using the edge of the film for registration and using post stabilisation for that instead (which has introduced some rocking). The other effect is the vertical (up/down) jitter. This is a function of a cyclic variation in perf pitch and weak pressure in the cart pressure plate (in varying degrees between) which scanners don't code for. This variation in perf pitch is not anything new in Super8 film. Have a look at the Nixon Kodachrome Super8 scanned on the Kinetta. One can see there is vertical jitter there as well - which you can see in the cyclic variation of the frameline thickness. But unless you are otherwise looking for it you could easily just miss it. And it would be even easier to miss if the image was cropped to the image area. None of these effects are "faults" as such. They are features. They are only "faults" if you don't like the effect. And if you don't like the effect then you can alter it, eg. by designing a scanner that uses the edge of the film for registration - and for vertical registration, designing a scanner that uses the same perf that cameras use, and for any remaining vertical registration issue, using a custom cart with a good pressure plate, or custom camera with the same. And then you will have atomic perfect registration in a scan. Otherwise if you're not going to do anything about any of these details - such as design, build or mod your own camera and scanner - or post-stabilise a scan using some art and technical know how - then there's no point calling these things faults. They become (or are) features of the tools you are otherwise using. This is the meaning behind a "good artist never blames their tools". A good artist either makes a virtue of their tools, as they exist, or they mod their tools to obtain a different behaviour (post-stabilisation being one such mod), or they make their own tools in the first place. C

-

As an add to the above, the history of effects in the cinema can be traced back to Georges Méliès and an important part of that history is that his very first effect is the result of an accident. But properly speaking the effect "precedes it's cause" (precedes the accident) in the sense that the effect proper doesn't occur in the accident but in the observation of the effect during a screening of the film. In other words it doesn't occur in any recognition of the accident, but in the screened effect. And without the effect the accident would simply remain an accident. The film would end up on the cutting room floor. But what the effect does is to transform that accident into what will then become the means necessary to recreate the effect. Now this is not to suggest that an effect can only be made by accident. It is to suggest effects be understood, firstly, in terms of an effect (what one sees), as distinct from their cause (this accident, that camera, this technique, etc). The task then becomes how to engineer the cause of such an effect. But the effect has to be an observable effect. Exactly those that accidents might otherwise expose. A form of precognition becomes required. To foresee an observable effect and to engineer it's cause. C

-

While experts might be able to determine, from clues in an image, the particular technical mechanisms involved, in the delivery of that image, it's really quite irrelevant. Either you know the delivery mechanisms (for example, you created the delivery in the first place) or you are hazarding a guess, based on experience. But a guess is always a guess. But whether it's right or wrong is really beside the point. What ultimately matters is not the delivery mechanism but the resulting image. If we otherwise put an emphasis on this or that way of delivering an image (film vs digital vs some other means) it is not out of any concern for whether an audience will guess the delivery mechanism (correctly or otherwise), but out of concern for what type of image we're delivering for that audience. We will know, from experience, that a particular way of delivering an image can deliver a particular type of image. And indeed we might learn there are other ways of delivering the same type of image - perhaps more cheaply. Or indeed we might opt to use a cheaper technology (for economic reasons) and due to limitations in such a decision, we alter the type of image we want to deliver, ie. in order to fit the technology we've otherwise adopted. We make the best of what we have - rather than trying to pursue a cheat in some insane way. That all said, I guess there's always something tantalising about a cheat. Cheats have a strange magnetic pull on our imagination. On one level they are a way of attacking the "reality effect" of photography - the idea that a photograph reproduces some pre-existing reality outside of the image. By creating a cheat one throws into question assumptions around photography (as reproduction of some real). But cheats can also reinforce that same reality effect. By turning an image into a trick, one can end up reinforcing the notion that images are inherently tricks - reinforcing the idea that reality is to be found elsewhere. But perhaps the most important aspect of any cheat is not that it is a cheat, but what the result might be: the effect. The effect is far more important than the means. But for this reason the means become important. For it is not enough to just create an effect that merely "looks like" the effect one is after. Such effects are short-lived. They can easily end up looking like nothing other than a wannabe effect. A failure. Far more interesting are those effects which are better than what one might otherwise be after - and this requires giving up, to some extent, the preconceptions that might otherwise motivate pursuit of a particular effect. It requires a certain amount of experimentation, and looking at effects for those which are of interest - and then using their associated means. The selected effect, in this sense, precedes it's cause. And there is no question of such effects merely "looking like" something other than what they are. For they are equivalent to what they look like (not less so), because they will have their origin within that very domain: the domain of the visible, the observable, the effect. C

-

I agree. Exploit each for their specific strengths, rather than banging one's head against a brick wall trying to erase any difference. Who buys a water colour painting because it resembles an oil painting, or vice versa? Some might do so but the majority certainly don't. Why bother trying to fool anyone? More often than not you just end up fooling yourself. The greatest illusion in films (acetate, polyestor or digital) is that films are an illusion.

-

CInematographers should not be paid... What?

Carl Looper replied to Tyler Purcell's topic in General Discussion

The domain in which "free" work takes place is a great domain. It's a world in which it's not about what large budgets can achieve. It's about what DIY filmmakers on shoestring budgets can achieve. It's the playing of an entirely different game, with entirely different criteria for success. It's about what filmmakers are doing within their means. And particularly those works which don't try to come off as being more than what was achievable within their means. The kind of work one does in this domain becomes a very different type of work. Or doing very different kinds of work are those that work best in this domain. What works when working on a shoestring? There are no awards (or indeed penalties) for how one might otherwise fake an expensive looking film. There are no penalties (or indeed awards) for how cheap a film appears. It's an entirely different ball game. C -

CInematographers should not be paid... What?

Carl Looper replied to Tyler Purcell's topic in General Discussion

I do free work all the time. And in between that I get paid jobs. The free work is on projects I love doing (as a creative person). The paid work I do, I would not do if I wasn't being paid. The paid work is typically work that must satisfy a large number of constraints beyond one's control. And it's typically a lot of pain involved (along with the pleasure). The free work - it's all pleasure (almost all). There's no real business logic in the free work. It's just purely for fun - if that's the right word. I get to make something with a bit more freedom about it - or at least something close to it. But in practice the free work does help out with the paid work. Someone sees my free work and says to themselves: well if you can do that then perhaps you are the person who can also do this (their task). There is always a bigger picture in play. Bigger than any particular project. C -

When I go ten pin bowling I can see the difference between that and playing the latest computer game, but I've never felt that such a difference would mean there was no longer "anything special" about ten pin bowling. It's not an either/or decision here. One can enjoy both. There's way too much of a "you're either with us or against us" logic that infiltratres consideration of these sorts of things. I've mentioned this many times before but it's worth repeating. When photography was first invented many thought it spelt the end of painting. Literally. Not just metaphorically. There was a huge consternation about it. It seems laughable today - and it is - but that's how photography was first received. As a substitute for painting. It was as if there was a choice to be made: between photography and painting. Some argued that painting was better because you could do paintings in colour. Ha ha. Photography would eventually resolve colour - because colour is interesting in it's own right - not because painting had that competitive edge over photography. The either/or logic that took hold of thought at that time was purely a false logic. Photography was a new art - not a replacement. Painting continues to this day and will no doubt continue for a long time to come. What was interesting at the time is that painters began to explore new ways of painting. Photography, in a sense, had initiated a liberation of painting. And photography, for it's part, found it's feet - not as some sort of automatic painting machine, but as making visible alternative conceptions of the world from that which painting made visible. C

-

There is a huge difference between film and digital, but some of those differences can be minimised, and some will argue it can also be elliminated. But it's purely a choice. Using film one might want to exploit what is different in film from video, ie. not just what is in common. Or vice versa. But either way one can't really ignore the difference. Not on a technical level. Well, one can, but it would limit what one might be otherwise able to do. It certainly involves the cinematographer's eyes but it's not just one's eyes. On a technical level one is working with materials that have their own kind of idea of how things work (physical forces) that need respecting. One might like to have a camera glide through a window, but the glass in the window will have it's own ideas on that. So one would be advised to take that into account. It's not all about a subjective point of view. It's not all about taste. It's also about how the world behaves. Or how it can be made to behave. It's not just the eye of the beholder. The beholden plays an equally important role - as obstacle and/or inspiration. C