-

Posts

22,410 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Everything posted by David Mullen ASC

-

Scratches/Rain on film

David Mullen ASC replied to Jed Darlington-Roberts's topic in General Discussion

It's abrasion but whether it is happening in the mags, the gate, or at the lab is the question... If you have two mags and it's happening in both, then it could be at the gate or at the lab, if you send a test to two different labs and it only happens in one, then it's the lab. Possibly you could run some fresh film and look at it with a magnifier without sending it to the lab just to see if it is the camera. Never done that myself so I'm not sure it would be visible on the surface to the eye. -

minus green gels for windows

David Mullen ASC replied to Joshua Kohler's topic in Lighting for Film & Video

The Van Gogh painting is greenish overall but only more so in the shadows, and the blacks... the "key" is the small yellowish-green lamp above the table. The issue here is what you are calling "the key" which should be less green than everything all around it. If the window light is the key, then it shouldn't be green or as green... but the problem is that this is not a low-key setting with a small source in the middle of the room surrounded by shadows -- the majority of the room is lit by window light. Will the subject be in the window light? Seems that this would be better as a night scene with a small yellowish lamp for the actor's face and greenish moonlight or dusk coming through the windows. Here's a quick attempt... imagine the person at the make-up table with a yellow lamp. -

I shot "Jackpot" in August 2000 using the Sony F900, which was the first 24P HD camera on the market. It was followed by other 24P cameras: I seem to recall a Panasonic 480P 24P (recorded at 60P) camcorder in 2000 just before the Varicam was released in 2001 and prosumer DVX100 in 2002. "Jackpot" was in the theaters in August 2001, two weeks before "Session 9", and several months before "Star Wars: Attack of the Clones", which got the F900 first. 24P HD was all the rage in independent filmmaking for awhile and then there was a lull until the next generation of 24P technology. The Thomson Viper came out in 2002 but was limited by data recording technology of the day. The Dalsa Origin was the first single-sensor 35mm-sized digital camera in 2003 followed by the Panavision Genesis in 2004. The Dalsa again was limited by data recording technology of the day (particularly for uncompressed 4K raw data) but the Genesis had the new 1080P HDCAM-SR tape format to record onto. In 2007 you saw the release of the Silicon Imaging 2K camera (16mm single-sensor) which recorded compressed 2K data and the Red One camera (35mm single-sensor), which could record compressed 4K raw data. The success of "Avatar" (2009) brought a wave of 3D digitally-shot movies and the conversion of movie theaters from 35mm to digital projection to show them. 2009 was also the year of negotiations over the new SAG contract, causing TV pilots to switch from film to digital in order to work under the AFTRA contract. I shot the pilot to "The Good Wife" that spring on the Panavision Genesis camera; the series (which I didn't shoot) used the Sony F35 until the ARRI Alexa came along. By 2010, the loss of TV shows that normally would shoot film was a big blow to the Kodak and the film labs in terms of the volume of negative processing; at the same time they both were dealing with the loss of 35mm print processing from the conversion of theaters to digital projection. So I would say that it was really in that period of 2009-2011 when the industry experienced the most change.

-

Style Ideas for Period Piece/Comedy

David Mullen ASC replied to Brandon Canning's topic in General Discussion

I think it is less of a case here, but the other issue with period comedies is whether you are also parodying the cinematography of period comedies -- an example would be a parody of a 1950s Hollywood romantic comedy where you copy the photographic approach. Otherwise, like I said, don't think of it in terms of "comedy lighting", just light the story for the required mood as if it were drama and make sure the camera set-ups and lighting highlight the joke in the scene rather than distract from it. -

Style Ideas for Period Piece/Comedy

David Mullen ASC replied to Brandon Canning's topic in General Discussion

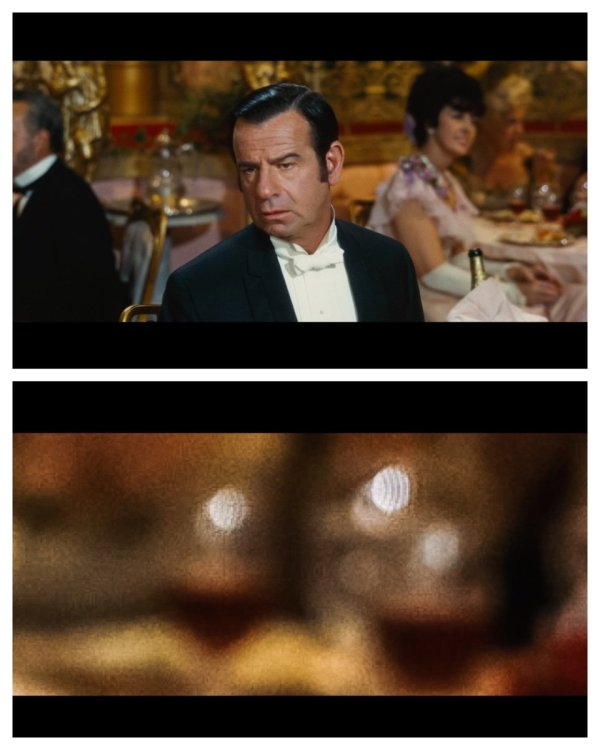

There are plenty of comedies set around the late 18th / early 19th century, from "Love and Death" to "The Madness of King George", or something shot by Geoffrey Unsworth titled "Royal Flash"... Personally I don't think of "comedy" as a visual style when I design the look for a comedy, the only rule about lighting and framing comedy is whether the humor is on display, can you see the sight gag, can you hear the joke, does the joke "land" visually, etc. -- or whether your approach is distracting from the humor. The other thing to keep in mind is that comedy often plays better in looser, wider frames in order to set-up the situation and interactions with props and people -- close-ups are more for drama and emotion. There are exceptions of course, the joke may land when you cut to a reaction shot for example. The most expensive shot in the Silent Era was the train falling into a gorge when a burning bridge underneath collapses in Buster Keaton's "The General" (1926), but in some ways that spectacular shot exists to get a laugh when Keaton next cuts to the deadpan reaction of the General who ordered the train to cross, saying the bridge would hold (played by the DP, Dev Jennings!) Other than that, it's better to treat a comedy just as you would a drama or romance, etc. Treat it straight, let the humor come out of the action and performances. -

Diffusion Filter Strength Based on Focal Length

David Mullen ASC replied to Ruth Vilas's topic in Lenses & Lens Accessories

I think some people noticed optical effects but in general there was less expectation for cinema to be seamless and technically flawless. But I'm sure there were critics back then just as today who didn't "buy" certain effects, did not find them convincing. Also keep in mind that print projection back then hid a certain amount of flaws. Some cinematographers were better at others at blending levels of diffusion -- I think Harry Stadling was excellent at that, whereas when Russell Metty put on a diffusion filter, it tended to really stick out. Some of it was the attitude at the time towards glamorization of close-ups; it was accepted as a convention, at least in the late 1920s, 1930s through mid-1950s. The widescreen and large format craze of the 1950s started to work against that. The desire to soften close-ups for the purpose of glamorizing the lead actress hasn't gone away, it's just that today you have more subtle digital tools to blur hairpiece/wig glue lines, reduce bags under eyes, erase blemishes, etc. And in the early days of DI's, it wasn't always subtle either -- I remember "The Island" (2005), where director Michael Bay seemed to have an issue with Scarlett Johansson's mole on her cheek and decided to blur it throughout the movie. On my show "The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel", we did not shoot close-ups, but in general there was a level of diffusion, usually from a 1/4 Schneider Hollywood Blackmagic. But I had to modulate that -- if we were shooting in hazed sets, the smoke would soften the image so I usually dropped back to a 1/8 strength. And for extreme long shots, I'd go even lighter to a 1/8 Black Frost or no filter at all. The thing is that today we have a lot more diffusion filter options and we can see the effect on an HD monitor on set, so it is easier to be more subtle when changing strengths of filters. In the 1970s, I think William Fraker was the closest in the U.S. to doing what Geoffrey Unsworth was doing with filters, though Fraker mixed his approach film to film based on the subject matter. -

Underexposed Face - Eye light

David Mullen ASC replied to Boris Kalaidjiev's topic in Lighting for Film & Video

People tend to look down so the light under the lens shows up better, plus I'm also using it to reduce bags under the eyes. The only downside is that is also adds light under the chin. Also I've found that people with deep-set eyes catch a lower eyelight better because their brow shadows a light over the lens unless it is a longer-lensed close-up. On a wider-angle lens closer to the face, the top of the mattebox can be too high relative to the face and the center of the lens. Plus the focus-measuring horns of the Preston/Lightranger are often up there. -

Diffusion Filter Strength Based on Focal Length

David Mullen ASC replied to Ruth Vilas's topic in Lenses & Lens Accessories

I address this with Ira Tiffen in the filter chapter of the 11th Edition of the ASC Manual. The reason for the contradictory advise comes from the fact that two separate issues are being conflated together. One: you need less diffusion on longer focal lengths to match the degree of softening from a purely technical standpoint. Some of this is probably due to how a piece of glass affects front focus on longer lenses, but also because you are looking through a smaller portion of the filter so whatever element in the glass is used to blur focus is being enlarged. Two: the tighter you go, the more diffusion you need because the viewer expects to see more fine detail in wide shots rather than in close-ups of faces, where too much detail can be unattractive, plus tighter shots tend to have less depth of field, so what's in focus naturally looks sharper being framed against a softer background, so can handle more diffusion. So in some ways, the safest thing is to just use one strength throughout (ignoring other issues other than shot size & focal length that affect perception of sharpness, like lighting contrast, amount of haze on the set, etc.) -

Overexposure gives the impression of less graininess because you expose the slower, smaller grains in between the larger, faster grains, so the structure "tightens" with a bit more exposure -- up to a point. Too much overexposure and you may start to see more highlight noise in the scan because the negative is so dense. However, 50D isn't really a stock made up of a fast and slower layer, I don't think -- there isn't much smaller, slower grains left to be exposed, it's already using smaller grains as a base. I've never found overexposure on the negative to increase contrast other than in contact prints because higher printer lights used creates better blacks... which give the impression of more contrast, more saturation. And again, with a lot of overexposure you start to lose contrast because so much highlight information is on the flatter shoulder of the curve -- something Conrad Hall used for effect in movies like "Tequila Sunrise" and "Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid." I once had a second unit DP accidentally load 500T when he thought he was using 50D, so he overexposed by over 3-stops. I could time it back down but the printer lights had to be trimmed to compensate and the look was a bit low in contrast.

-

Emulating 5263 with 5219

David Mullen ASC replied to adrian angehrn's topic in Film Stocks & Processing

Probably 5263 pushed one-stop looked like 5219 with no push, contrast-wise, but softer and grainier... So how to increase the grain of 5219 without pushing, which would add contrast? Perhaps just underexposing would be enough. -

Interpreting this Sensitometric Curve

David Mullen ASC replied to Chelsea Craig's topic in Film Stocks & Processing

I wonder that too... 20 years ago or more, I would have said you would want to film out vfx, digital titles and transitions back to S16 negative to cut into the original negative for making an optical printer blow-up to 35mm... but no one does that anymore, so what's the point of a film recording back to S16? -

Is it common to use prores on the Sony Venice 2?

David Mullen ASC replied to Edith blazek's topic in Sony

I've used ProRes 4444 Log on every TV series I've ever shot on Alexas and the Alexa 35 now, except for the occasional raw recording for VFX or some other reason. But I just shot a small feature on the Alexa 35 and we recorded Arriraw.- 5 replies

-

- sony venice

- prores

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

What are you people doing with your scanners?

David Mullen ASC replied to Daniel D. Teoli Jr.'s topic in Post Production

- 7 replies

-

- 3

-

-

-

- betty brosmer

- scanning

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Goodbye remjet, hello AHU?!

David Mullen ASC replied to Joerg Polzfusz's topic in Film Stocks & Processing

It will mean though that all the people who shoot Cinestill film for that red halation around lights (because of the removal of remjet so no anti-halation backing) will be unable to get that effect anymore. -

Late 1960s and Early 1970s Filters

David Mullen ASC replied to Joe Taylor's topic in General Discussion

-

Late 1960s and Early 1970s Filters

David Mullen ASC replied to Joe Taylor's topic in General Discussion

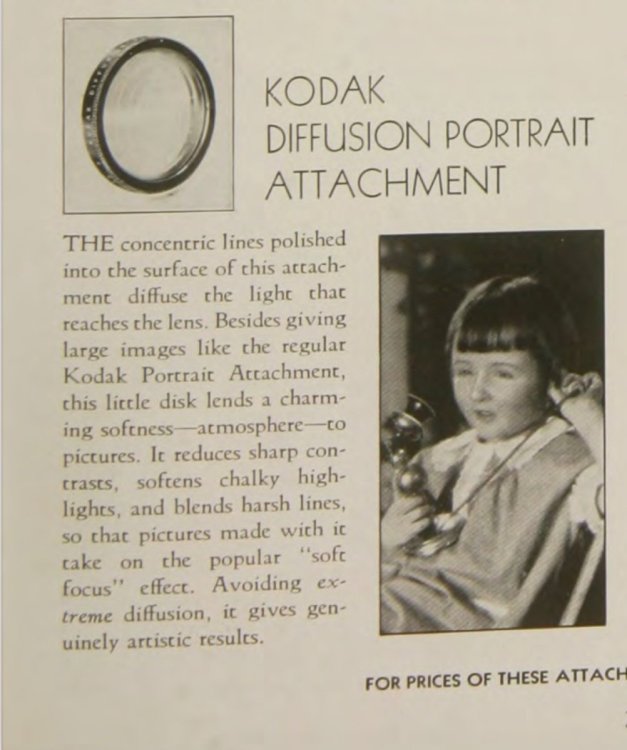

Harrison started selling Fog and Diffusion in the late 1930s. Their Diffusion is sort of a mist filter I believe meant to compete with the more variable (in manufacturing) Scheibe filter of the 1930s. The most common diffusion filter for close-ups (besides nets) was the Kodak Portrait Diffusion Disk, which seemed to stop being used by the end of the 1960s. Kodak diffusion filters go back to the 1900s I believe, first used for still photography and in enlargers making prints. Mitchell diffusion appears also in the late 1930s. The design was revamped in the early 1960s when Panchro started making them. Tiffen started being popular for cinematography in the 1970s — I suspect in the 1960s they first catered to still photographers. Schneider Classic Softs are a variation of the old Hasselblad Softars. Perhaps the Tiffen Fogs, Low-Cons, etc. of the 1970s were slightly less blue in the halation than Harrisons but not by much. -

My dad took a lot of color slides while in the Navy in the early 1960s, stationed in the Philippines and Japan -- the Ektachromes faded to pale magenta but the Kodachromes got eaten by mold in the Philippines, dark spots everywhere -- I guess they liked the dye! The colors are still great though...

- 5 replies

-

- film degradation

- archive

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Is there such thing as a commercial look?

David Mullen ASC replied to silvan schnelli's topic in General Discussion

There isn't really a specific "commercial" look nor a "narrative" look, there are many looks. However, since the main point of a commercial is often to sell a product, and there are certain styles in commercials that repeat themselves (like the golden sunny kitchen light for an orange juice commercial), when one is shooting a scene with a car, let's say, and the director says something like "I want this to feel like a Porsche commercial", i.e. show off the car, make it beautiful -- or converse, complains that the shot "looks like a car commercial" -- the cinematographer gets the drift. -

The Brutalist - shot by Lol Crawley

David Mullen ASC replied to Stephen Perera's topic in On Screen / Reviews & Observations

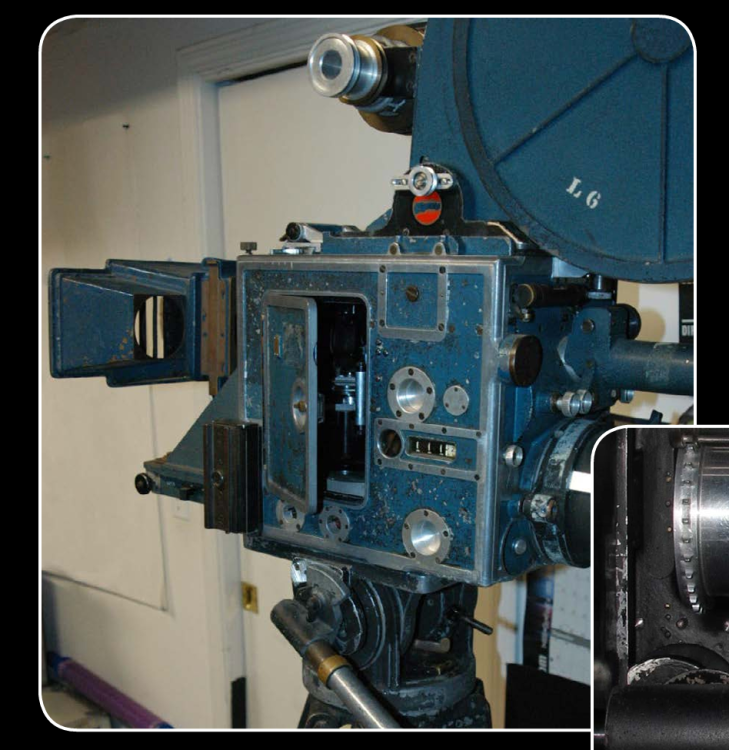

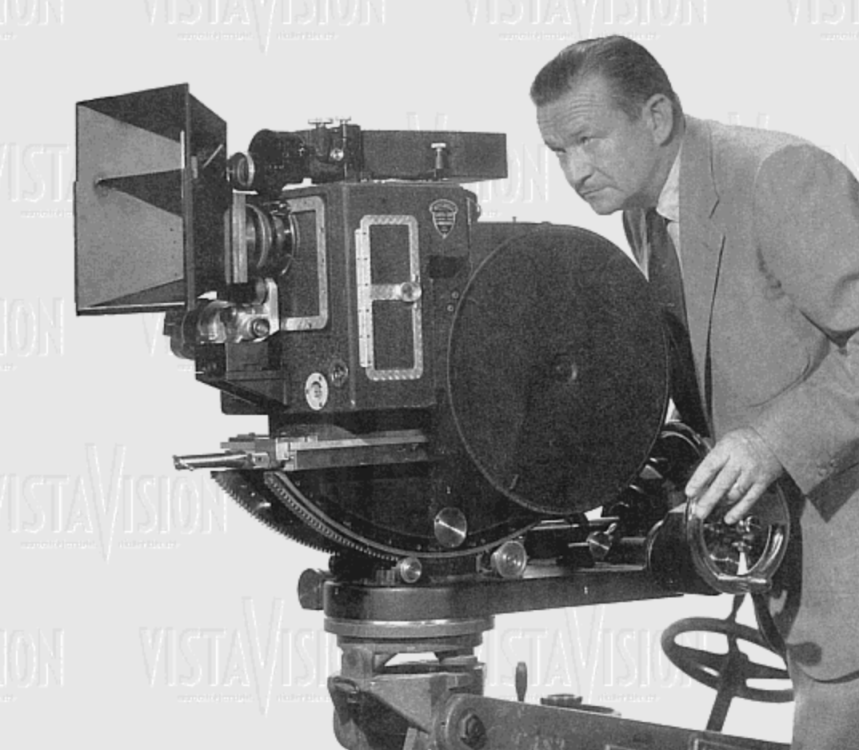

You can see the operator side of an 8-perf 35mm Technirama camera here -- it's not quite the same as the Mitchell elephant-ear VistaVision camera. This article says that Paramount converted some 3-strip Technicolor bodies to VistaVision but that the Mitchell elephant ear camera was a separate camera: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/vistavision-searching-history-mark-pollio#:~:text=There were eleven 3-strip,one known as elephant ear. -

The Brutalist - shot by Lol Crawley

David Mullen ASC replied to Stephen Perera's topic in On Screen / Reviews & Observations

The Technicolor camera bodies were converted to 8-perf 35mm for the Technirama process with the magazines usually on top -- though the Mitchell elephant ear VistaVision cameras look very similar I don't think they were made from a 3-strip Technicolor body. Though I acknowledge that Mitchell built both types of camera bodies. -

Just depends. If the 4x4 frame is not too heavy, like an Opal, and would be larger relative to the subject compared to the distant physically larger frame, then sometimes that works as a fast way of softening the key further. But if the 4x4 frame wasn't going to be any larger relative to the other frame, then the light isn't going to be much softer unless that larger frame was too light so the lights behind it were creating hot spots rather than filling the frame, but at that point you'd be better off just adding the 4x4 frames between the lights and the large diffusion to make the light fill it more evenly, because it's the size relative to the subject that determines softness. If the 4x4 frame was relatively larger compared to the distant frame but you wanted something heavier like Full Grid Cloth, then you'd probably add some light behind it to compensate for the light loss. And sometimes you might want to bring it slightly forward to wrap around the face a little more too, so that would require both a diffusion frame and a light behind it. There are no rules.

-

La Double Vie de Véronique Film stock

David Mullen ASC replied to Jorge Castrillo's topic in Cinematographers

It was shot in 1990; the year before Kodak came out with the first EXR version of their fast film, 5296 500T, so it probably was shot on that -- though it was possible to still buy the older high-speed stocks, 5294 and 5295. The EXR series was the first to use T-grain in all the layers. 5294 400T came out in 1983 before T-grain technology but was still being used by a few people as late as 1991 ("Bugsy" for example). 5295 400T came out in 1986 and used T-grain for the blue layer and was sold as a high-speed "bluescreen" stock. For a few years, it was a case of some DPs preferring 5294 and others 5295 (a bit less grainy but also a bit more contrasty, plus Kodak charged more for it). https://www.kodak.com/en/motion/page/chronology-of-film/